A History Of Black Banks From 1888-1930

Are you familiar with the concept of “Big Bank Take Little Bank?”

Rap artists, from Ice Cube to 2 Chainz, have amplified this phrase as a succinct depiction of the harsh realities within the financial world, where larger banks and affluent individuals exert their dominance over their smaller counterparts.

However, this game has a rich historical background, tracing its origins back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During this time, African Americans, acutely aware of the transformative potential of formalized financial systems within a capitalist society, established thriving banks and insurance companies. Visionary pioneers, lacking access to white-operated banks and opportunities for clerical and managerial experience, embarked on a journey of trial and error. The resulting institutions, both large and small, emerged as beacons of liberation, defiantly challenging the pervasive grip of deeply rooted racism.

Prior to Emancipation, the establishment of Black-owned banks in America was non-existent. However, on the eve of the Civil War, free Blacks residing in the North engaged in discussions about the importance of credit and banking and began exploring avenues to establish such institutions.

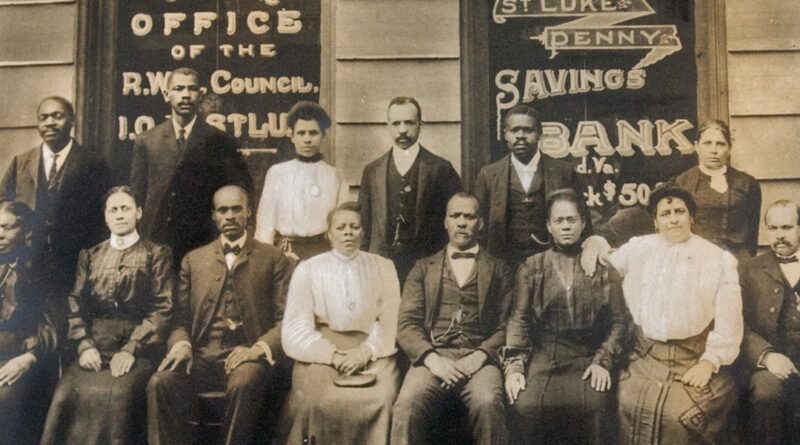

In the face of exclusionary practices and discriminatory Jim Crow policies, African Americans took matters into their own hands. Between the years 1888 and 1930, they demonstrated remarkable independence by organizing and operating over 100 banks, along with thousands of other financial entities, that catered specifically to the needs of their communities. These customer-centric banking systems bolstered successful entrepreneurs and safeguarded Black businesses and individuals who were routinely robbed by white predatory practices and terrorism. They also provided a source of credit, loans, economic development, jobs, and training opportunities for their communities.

The rapid growth of Black banks, which allowed Black wealth to stay within our communities and even outperformed some larger white institutions during financial panics, marked a monumental achievement for the first generation of emancipated people.

An editorial published on May 16, 1914, in The Denver Star remarked: “How the Negro has succeeded in this branch of business without previous experience,

without a coach and even without the semblance of encouragement is really more surprising to white men than to the Negro himself.”

Yet, the success of these institutions, such as those along the prosperous district Tulsa’s Black Wall Street, made them prime targets for racism and violence, laying the groundwork for our present-day profound intergenerational consequences on Black wealth.

Presently, we witness a stark reality: Blacks remain more unbanked or underbanked than any other racial group. Our reliance on fringe banks, often ensnaring us in cycles of debt, is a distressing truth. Additionally, we contend with higher interest rates on mortgages, small loans, and basic services compared to our white counterparts. The decline in the number of Black-owned banks, dwindling from their peak of 100 to a mere two dozen today, stems from consolidation within the banking industry, mounting regulatory burdens, exorbitant compliance costs, limited access to capital, and the persistently higher unemployment rates and lower wages prevailing in our communities.

However, this is not yet another story about Black suffering, failure, and repeated injustices, although these forces undoubtedly form a crucial backdrop to any historical reflection on Juneteenth. Instead, this is a moment of celebration and spotlighting the early organizing efforts and heroic struggles of individual Black bankers, who despite their limited or nonexistent access to the circle of finance, emerged triumphant in their quest for racial uplift.

As we delve into the annals of history, particularly through the pages of esteemed Black media outlets such as The Nashville Globe, The Crisis, The Cleveland Call and Post, The New York Age, BLACK ENTERPRISE, and others, we can see how Black people made it a point to celebrate their hard-won successes. An inspirational narrative unfurls before our eyes – a tapestry woven with threads of triumph, resilience, and unabating dedication to the achievements of Black financial institutions. Through these reports and impassioned editorials, we witness a profound story that transcends time—one of unwavering racial pride, Black protest and unity, and the pursuit of self-determination.

“Blood and Tears”

Emerging from the shackles of slavery with their spirits unbound, millions of formerly enslaved African Americans had little grasp of the intricate operations of businesses and banking institutions. After all, these were a people who were deprived of self-ownership, as they were legally defined as human chattel for three centuries.

The bodies of enslaved people were used as collateral for thousands of mortgages and to finance the acquisition of land or goods, serving as a haunting reminder of their commodification. Reduced to mere transactions, enslaved Blacks were traded to offset debts or torn apart from their children who were callously handed over to creditors by the merciless hands of the courts.

While slaves were forbidden to own anything, free Blacks residing in the north had faced limited opportunities for wealth accumulation due to pervasive discrimination. Undeterred, they formed mutual aid societies and fraternal organizations which provided financial assistance and social networks. These organizations pooled money to ensure dignified burials, extended monetary aid in times of need, and fostered economic cooperation and solidarity among Black communities. Black leaders like Frederick Douglass and David Walker used their platforms to advocate for equal rights, access to education, economic justice, and to promote self-reliance.

“America is more our country, than it is the whites—The greatest riches in all America have arisen from our blood and tears,” proclaimed Walker in his influential 1829 “Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World.”

“America is more our country, than it is the whites—The greatest riches in all America have arisen from our blood and tears,”

-David Walker

Douglass remarked that “the history of civilization shows that no people can well rise to a high degree of mental or even moral excellence without wealth. A people uniformly poor and compelled to struggle for barely a physical existence will be dependent and despised by their neighbors and will finally despise themselves.”

Walker expressed the belief that African Americans had played a significant role in building the wealth and prosperity of the United States through their forced labor and suffering under slavery. Meanwhile, Douglass believed that without wealth and economic stability, Black people would face constant hardships, leading to dependence on whites and a diminished sense of self-worth. For Walker and Douglass, wealth would not only provide material well-being, but also enable Black individuals and communities to pursue higher ideals, intellectual growth, and moral progress.

Not surprisingly, the transition from bondage to freedom was marked by poverty, insecurity, and violence. Emancipated slaves found themselves trapped in a state of destitution, lacking financial resources and access to formal employment opportunities. The institution of slavery had systematically denied them the ability to accumulate wealth, property, or monetary savings. They often had little more than the clothes on their weary backs and lived in dilapidated and overcrowded housing, with limited access to safe and sanitary living conditions. Some former slaves resorted to squatting on abandoned or unclaimed lands or lived in makeshift shelters.

Freed slaves faced significant obstacles in securing employment. Many were coerced into continuing their toil on plantations or in other agricultural labor, subjected once again to exploitive conditions reminiscent of their time in slavery. Others sought employment in cities and towns, but faced discrimination, low wages, and limited opportunities for advancement.

African American’s initial experiences with formalized banking as a collective began during the Civil War through military savings initiatives which granted Black troops the opportunity to save their pay. The culmination of these efforts materialized in 1865 when Congress established the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, known as the Freedman’s Savings Bank, headquartered in Washington, D.C. With 32 branches principally located in the South, this visionary institution attracted over 61,000 Black depositors, channeling over $55 million to their quest for financial security.

Initially, the bank was decently run. However, a pivotal turning point arrived in 1870 when the bank’s charter was amended, permitting investment in risky real estate mortgages. This amendment marked the beginning of a tumultuous period for the institution.

The bank’s leadership became entangled in speculative ventures, embracing high-risk investments, often without proper due diligence. Those investments were not always aligned with the best interest of depositors. The absence of robust oversight and regulator mechanisms, coupled with inadequate supervision of bank officials, resulted in mismanagement of depositors’ funds. Henry Cooke, the bank’s president, and other officials engaged in self-serving practices, extended loans to themselves, their associates, and family members without sufficient collateral or evaluation of creditworthiness.

Furthermore, the economic upheaval of the post-Civil War era, including the Panic of 1873, had a significant impact on the bank’s financial stability. The culmination of these factors resulted in the defrauding of thousands of Black depositors who had entrusted their savings and hopes for a better future to the Freedman’s Savings Bank. The failure of the bank and the subsequent loss of funds dealt a severe blow to the economic aspirations and progress of African Americans at that time. It served as a clarion call for the establishment of stronger safeguards and regulatory oversight within financial institutions, essential pillars of financial justice.

When Frederick Douglass was appointed as the last president of the bank, he remarked that the institution was, “the black man’s cow but the white man’s milk.”

“the black man’s cow but the white man’s milk.”

-Fredrick Douglas

Reflecting on this era, the eminent civil rights activists, W.E.B. DuBois, mourned the consequences of the Freedman’s Bank’s failure, stating that it “not only ruin[ed] thousands of colored men but taught thousands more a lesson of distrust which it will take them years to unlearn.”

But the story of Black banking did not culminate with the disastrous failure of Freedman’s Bank, which left a staggering debt of over one million dollars to its depositors at the time (equivalent to around $30 million today).

Despite the profound disillusionment caused by the bank’s demise, Black communities still held the institution in high esteem. At a time when opponents argued that ex slaves were incapable of self-sufficiency, the existence of the Freedman’s Bank served as undeniable evidence that they could indeed thrive.

Resilient and undeterred, Black people refused to rely on the slow progress of justice. Instead, they charted their own independent path in the realm of banking, leveraging their collective ingenuity and unwavering determination.Celebrate Juneteenth 2023 with BLACK ENTERPRISE with month-long content that explores the history of prosperity and banking, and the future of investing and financial literacy for Black communities.

READ NEXT: Banking On Self-Reliance: A History Of Black Banks From 1930-Present